THROW YOUR PHONE INTO A LAKE

Pushing back against the frigid efficiency of catch-all technology, Evening’s Osebo talks designing for one pure purpose: streaming live audio, anywhere.

Osebo and I first got connected through my creative partner Matt Pecina of Studio Guapo (if you read Designheads, you probably are familiar) — Matt invited him to join the Designheads launch party to DJ on behalf of Evenings, the project based around a live streaming device Osebo’s been developing along with his creative team.

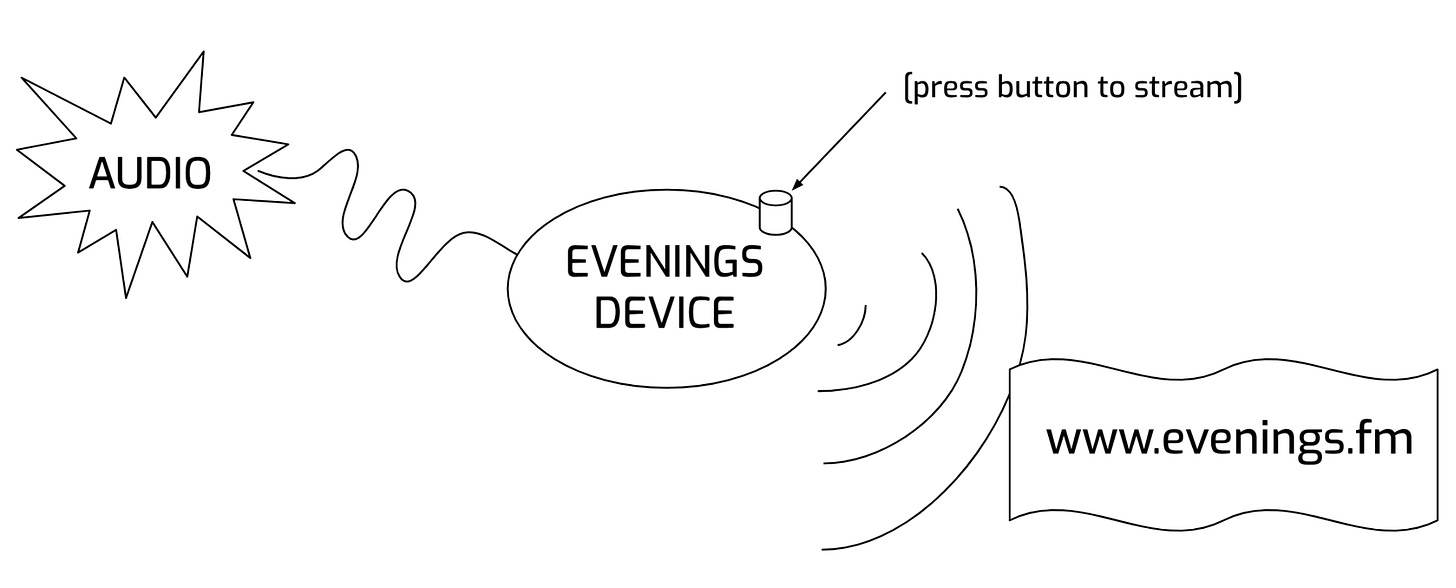

The Evenings device has a single function: plug it into an audio source, press a button, and it automatically livestreams your audio out via www.evenings.fm. Intended for seasoned DJs and beginners alike, Evenings is a harbinger of a larger trend in tech: as we reach functionality saturation in our smartphones, inventors and innovators are putting the gears in reverse, embracing technology and platforms that lean into more narrow functionality.

Substack, the platform we use here, is a great example: their straightforward blogging and subscription platform offers a streamlined tool for sharing text and images with limited options around appearance and format.

But limitations aren’t necessarily a bad thing, especially in the case of Substack — they allow us to focus on what we want to do: to share stories and profiles that relate back to radical design culture. And in the case of Evenings, the simplicity of the device is the draw itself. Osebo describes it in the language of a talisman or lucky pebble: an object to be carried around and pulled out when needed to fulfill its simple task.

After we got connected, Osebo and I corresponded a bit on Instagram around object design — specifically perfume bottle design, like the various iterations of the popular COMME des GARÇONS bottle (see below). The palm-ability of objects like these is mirrored in the design of the Evenings device—a yet-to-be-revealed portable piece of tech shaped not unlike a river rock.

All of this piqued my interest, and I pinged Osebo to see if he would be open to an interview. We got together over Zoom to talk big concepts and interfaces, and Osebo also was kind enough to send over a plethora of imagery from the team’s creative development process, which we’ve included below.

First question! Can you give us an overview of Evenings? That’s how we got introduced.

Broadly, I'm a designer. I've worked between digital and physical products. Early on, I worked at Tumblr as an interface designer more or less: a product designer. I worked on things such as the camera or the way you post images or videos, and a bunch of other wacky ideas that didn't quite make it out.

I even worked on a sort of VR-like, spatial version of Tumblr that was pretty experimental. It was a really interesting and fun way of digging into spatial design, in a really early sense. I later joined Oculus, specifically to work on VR for live events. There's been a through-line in my work: I've focus on creative tools that enable people to express themselves and build community.

In the context of Oculus, I was working on event spaces and live VR, like concerts. But most recently I've been working on Evenings. (I also work for Nike, where I've been working on virtual collections, essentially.)

Evenings has really been something that stemmed from the post-pandemic period: there were a bunch of internet radio stations popping up in San Francisco at the time where I was actually living during the pandemic.

I don't know if you've heard of Hyde FM or Lower Grand Radio … There's a bunch of independent radio stations growing. It's really a way for people to form community around a specific genre or sound that they want to push.

It's beautiful, because people put in so much effort and created these really janky setups to get an internet radio station going. Hyde FM, specifically: their station was in the middle of the Mission District on 16th Street, on the corner. It wasn’t the “best” area, but people would still go to the spot and congregate and like really just jam: play music and host parties, towards the end of the pandemic, which is what brought the community around it.

But in that process, I really saw how broadcasting and recording high quality audio is a really cumbersome process. You have to use an audio interface, you have to use a computer — there's just all these different aspects that make it inaccessible to a lot of people. And for that reason, a lot of people don't do it. It really takes a community to get started, it takes a village.

Taking a step back: there's a group of people that I DJ with, called New Nostalgia, and the other two are back on the west coast, while I’m here in New York. We would host a ton of shows and Brendan Luu would want to stream some of these live sets that we would put on during the pandemic, in our house (we used to live together). And just the amount of setup it would even take to do that is what really inspired this project — that was the catalyst.

Even just thinking about it, in some sense, it's beautiful: being able to go to a live show, being in the moment, and just experiencing it. You're like, “Wow, this is fucking incredible and I'll never be able to experience it again.” But sometimes, I'm also like, “I would like to experience it again.” [laughs]

So, how do we make that more accessible and easier for people?

Putting that autonomy in the hands of the people who are playing the music is really interesting to me — versus having some sort of person in the middle. This all brings up a lot of interesting questions for me.

One thing I think a lot about is the reverse funnel that’s happening in new tech where, in the past, we were working toward having everything on our phones, but now there’s an increased interest in diversification: people are creating sort of artisanal technologies or products that do one really specific thing.

Do you notice this happening as well? And why do you think that’s happening?

Yeah, that's exactly it. A smartphone is really just a vending machine.

It started as this thing that had very specific utilities. You can call someone, you can text someone, etc. I’m thinking less of a smartphone, but more of what came before that. But then, as they became mini computers, their capabilities became unfathomable and they're still evolving.

But I think we're getting to this age where we're realizing, “Oh, I don't actually need my device to do every aspect of my life.” Maybe there are things that the smartphone can't do perfectly.

And that's actually part of the problem we're trying to solve. You can't plug your phone directly into an audio source — you actually need an audio interface.

An audio interface is beautiful too, because it actually is a utilitarian object that's completely offline and does only one thing, similar to a hammer.

That was the hypothesis, the underlying idea for what we're building with Evenings: we're trying to create something that is sort of invisible, where there's not much of an interface. We even had discussions on whether there should be an interface at all.

It’s essentially something that you just plug into a DJ controller, a synthesizer, or anything that can emit audio. You press a button and you can leave it and forget about it and be present in the moment.

When you're on your phone, you're not very present — you’re online, which is the opposite. So it’s about being able to record and broadcast and do what you're already doing and connect with people who may not be able to physically be there and to archive that moment … but still be in the moment that you're already in.

It makes me think about how, in our homes, it’s perfectly normal to have an object that does one thing or has one purpose, like in the kitchen. Like I have a martini shaker by Michael Graves, and I love it because it just does this one thing and it’s lovely to look at.

But part of that thinking is about a mindset shift — moving away from equating pure efficiency with pleasure or quality of life. Having everything in one place doesn’t necessarily mean our quality of life is better.

We've been thinking about it even in the way we've designed the Evenings device. There's two components: a hardware component and a software component. We’ve been thinking about it with three metaphors.

There were three metaphors that were used — one was the monolith, which is this formal structure that has a monolithic body. But it almost felt too rigid — it didn't feel very approachable. It didn't feel like something that you wanna bring with you.

And then there was this idea of a puddle: something that can capture things, something that feels sculptural in a way and has like a clear area for you to interface with, but has contrast with the rest of the body of the object. And that felt decent, but what surrounds it [in the puddle metaphor] wasn't entirely clear.

So there was a final direction that we have, which is the idea of a bioluminescent object/bioluminescence; something that felt softer, more handheld, and also encompasses light. That's one of the core parts of the product: when you go live and you're recording, there's a red light that shows up and illuminates the whole device.

It almost feels like this big glowing red rock. But yeah, that’s where a lot of the inspiration came from. And if you think about the different radio stations that are coming up — we want not just communities of people to be able to use it, but individuals as well.

I love that you all are tapping into the physicality of the piece too, because there’s something there — this idea of a sort of pebble you carry with you, a lucky object. It makes me think of when I was a kid and how I would collect river rocks and have them in my pocket, and you sort of touch it and it fits perfectly in your hand.

It’s almost gamified — not in the way you interact with it, but like the role it plays: like in Zelda or Pokemon, where you pick up this magic object that does one special thing for you.

Beyond the broader concept, how did you all go about designing the physical body of the Evenings device?

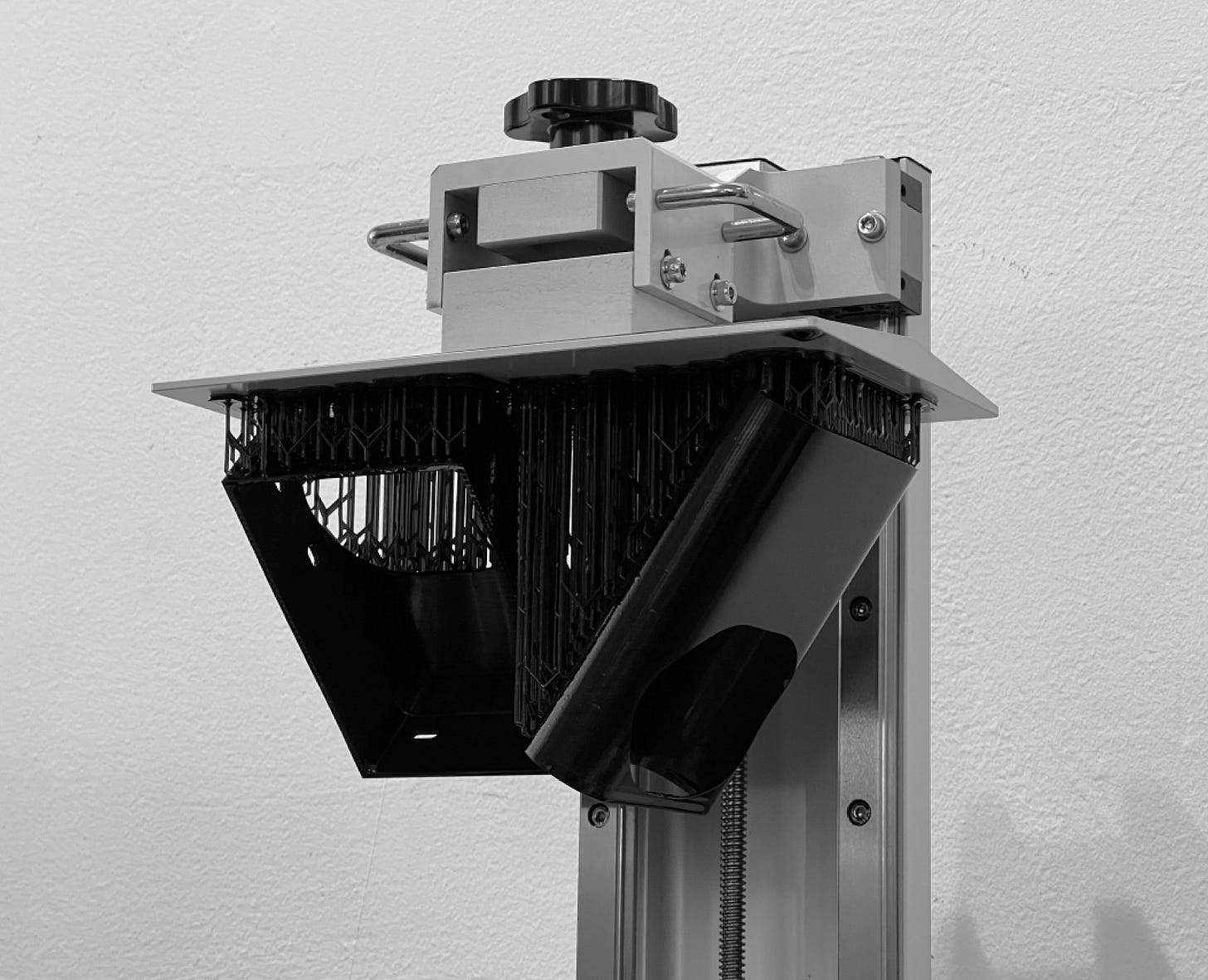

A lot of it was just shopping ideas around with our community and getting people to be really honest. We did tons of 3d prints, sharing it in organic contexts, asking, “So you’re at a show or at home and you’re using this — what do you think?”

People's initial reactions gave pretty clear feedback. But I think, even just beyond that, the reality is that producing hardware is a pretty ambitious thing to do, which is why companies like Apple continue to reign over the market. Maybe there's like one component available that you really need for your hardware product and then some behemoth of a company buys every single unit of it. What are you supposed to do?

We ran into issues like that, also with the shape of our product. People see the straight edges of an iphone and machined casing and they feel like it's something that is “premium” — when it’s really a pretty affordable way to produce something of that nature. They’ve shaped our perception of beauty and luxury.

But then you take things that are more complex in shape, like what we're working on: something that feels more like a rock and that's also more expensive to produce. There's just a lot of production considerations that we have to think about as we've been going through the process. But we've been learning a lot and, once again, it takes a village — Niko Lazaris (software), Cyril Engmann (electronics), Kebei Li (design), and Jimmy Young (design) — I'm not doing this by myself.

It’s really something that can be passed around and shared amongst people to form one entity — something like NTS Radio. But you can also be alone and be an NTS too.